https://main--cc--adobecom.hlx.page/creativecloud/img/icons/painter.svg | Painter

Mar. 29, 2022, by Roz Morris

Inside the Floating Spaceman: A Portrait of Cornelius Dammrich

Roz Morris and Cornelius Dammrich discuss the processes and experiences that bring out his creations.

Cornellius’ work with Substance

“Gamma”

A black space. Travelling out of the darkness, like a piece of space-junk, is a cluster of cathode ray tube monitors, lashed together with tape. Before flatscreens, these hulks were everywhere, in our homes and offices. How could they seem so strange now?

This enigmatic piece is the work of Cornelius Dammrich. He created it for Substance in May 2021 and describes it as a love letter to his first PC.

‘I was born in 1989,’ he says. ‘I still vividly remember my first computer. It was yellowish and slow with 28 Mhz and it housed all the magic and excitement there was in this world. I was just 6 years old but immediately knew that I would become a computer person.’

Monitors

And here they are, the monitors that fell into obsolescence, on a mission of their own, still working, winking mathematical shapes into the darkness.

Devices

Devices are one of his big motifs, and he uses them to create an epic sense of entropy. A cat sits beside a clock radio a few minutes after Armageddon. Space men visit old telephone boxes.

Octane

You might already know this one – if you use Octane, look for the floating astronaut on the load screen.

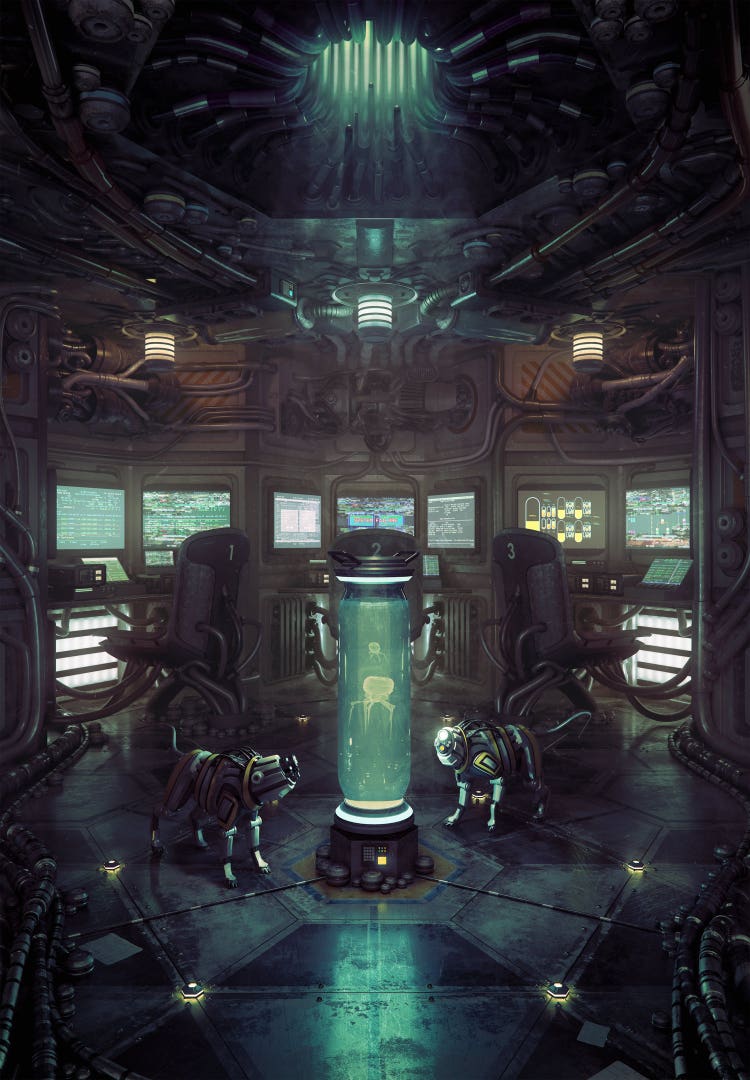

6088AD

You might know this one too, titled 6088AD. Cornelius made an hour-long YouTube tutorial about its creation and it’s been viewed over 100,000 times.

His pictures have a deep awareness of time moving on. Here are those CRT monitors again – this piece, Ancient Area Network, made in 2011, was inspired by LAN parties he used to hold with school friends. Though he is at pains to point out that most of their gatherings were somewhat smaller than the vast hall in the picture.

Grunge aesthetic

Cornelius was born in East Berlin just before the Wall fell. I draw the obvious conclusion, that this must be the source of his grunge aesthetic, his appreciation of use and age. There must have been a contrast between East and West Berlin.

He dismisses my suggestion good naturedly.

‘The Wall fell when I was one year old. I didn’t see a lot of the communist part of Germany. But my family lived there for many years, so I grew up with stories about Soviet Germany. After the Wall fell many people left East Berlin. There were buildings that were empty. You could open a door, tell the landlord you wanted to live there and it was yours. We moved into a flat with high ceilings, really old fittings. An apartment like that would go for millions today.’

But the lucky find was shortlived. One day they came back to find the building had burned down and their rescued belongings were on the street. ‘We climbed the stairs. They were thickly layered with ash, pressed down and wet from the firehoses. We climbed beyond our apartment and there was just the night sky because the roof was gone. I was told the landlord burned it down for insurance money. Then we moved to a much nicer flat because we got insurance money ourselves.’

Still, I want to know more about his remarkable eye for old spaces, thick with the marks of life. Here’s Exhibit A.

He laughs. ‘It’s just what I like. Creatives are a product of the things they’re inspired by. So if you like a book, you’ll be inspired by it, even in tiny bits. And I am inspired by dirty or used stuff. The really clean stuff without fingerprints and scratches is boring. Of course, I appreciate new when I’m unboxing my new iPhone, for example, but when I create an artpiece …. If I build a water bottle, it’s boring if it’s new. It should be banged up and worn.

‘I was always like that. When I was 9 or 10, I found a book in the rubbish bin of a neighbour. It was by HR Giger, who designed Alien. I was like, holy fuck, this is a thing? There are people painting aliens and biomechanical worlds, all gory and creepy? Everything that was a little bit fucked up I was interested in. Also morbid stuff. I read about serial killers and medieval execution methods. But I’m not a psychopath, I find it super-interesting. Why do people do things? History is violent and history is interesting to me. I like knowing things from the past.’

On his website he mentions a period when, as a kid, he painted the sinking Titanic, again and again, in MS Paint. That, he says, started after he saw the James Cameron movie.

‘I was obsessed with that movie,’ he says. ‘I drew it obsessively, the boat sinking and the bodies floating… I did like 20 pictures of it. I was a weird kid.’

Until The Light Takes Us

Look at the notes on his work and you’ll see a lot of back story. Why 6088AD has a figure in the shadows with a baseball bat. Why the aircon ducting looks the way it does. I ask if this is a desire to tell a story with the work. He considers, then says no. It’s how the image grows. It develops its own reality as he creates it.

‘At the beginning I don’t think about a story I’m going to tell, or a meaning. The initial idea comes from a visual feel, an atmosphere. Then I tackle the tech problems.’

He tells me about Until The Light Takes Us – two wolves in a space station, hunting the sun and the moon.

‘With that piece, I was having problems with the framing and what should be in the centre. That process took me into mythology and it became the back story. When I start an image I never know how it will turn out. Over time, the story evolves in the image. With every day I work on it I give a piece of me to the image to make the image speak to me more.

‘The inspiration can be music, a still from a movie, a photo. For 6088AD, it was a village in Greece, painted completely blue. Then I came to London in 2016 and on the train from Heathrow, I looked out and there were so many pipes and cables tethered beside the train track. We don’t have that in Germany. I enjoy cables… So I combined them with the blue Greek village. There were hundreds of other little influences – the story of the astronaut and the two people in the shadows who want to rob him. And the picture has an orange part and a blue part. All that came during the process. But it started with the Greek village that was blue and the pipes on the train track into central London. That’s how I do my pieces.’

The pieces grow slowly, over many months. 6088AD took nearly a year. But the detail is engrossing. If you zoom in you’ll see more and more, almost into infinity. You can enlarge the detritus on a table, the graffiti on a wall of a telephone kiosk. He likes the viewer to explore, like the photos in Blade Runner.

At this point, I leap out of my seat (and am yanked back by my headphone cable). I know what he’s going to say. When I was 8 years old, I went to Cologne cathedral. It has a gold casket, which contains the bones of the three kings who visited baby Jesus. When I went there, I was insane with curiosity about it. None of the adults around me were interested. Now here’s Cornelius, eager to tell me what I missed.

For a while, we happily geek out. Cornelius tells me the casket was opened in the 1860s. ‘It was wrapped packages and bones.. a jawbone and teeth and stuff like that. Holy fuck, if that ever happens again I want to be there!’

Me too.

‘I want to open every sarcophagus in that place,’ he says. ‘It’s creepy but it’s history. Is there something there? There’s something from the Children’s Crusade in there. Perhaps in that golden shrine. I want to know! It’s the same thing with art. I want to see everything. All the little cracks. I want to see it all.’

I could talk to him for hours like this. He’s full of a sense of deep time surrounding us like air, at molecular level, ticking, transforming. That’s the nature of the dust and scuffs in his paintings. It’s a touchable connection to each moment of the past.

We talk about joy and curiosity, how they are the life-source of creativity. The sense of play, of following your interest, no matter how kooky. This is how we invent ourselves as artists.

He says: ‘When I started making art, I was 14, 15. I wasn’t thinking I’d make a living at it. Art was a hobby. After school I came home, played video games and tried to make something in my 3D software. It was goofing around, there was nothing serious about it. I became better and started to think, I’m good at this… and not good at anything else. Maybe it’s how I could make a living.’

Freelance work

He went to design school, then took a job in an advertising agency. ‘I thought it would be the best thing, but found it was the worst. I was working in architectural utilisation. Architects gave us a 3D model of a housing complex, a mall or an airport, and we put people and textures and trees in, so it looked real for an advert or a board on the construction site. I hated it. My colleagues were nice but the workload and the company were horrible. I was there seven months. Then I was a freelancer for six years. I created all sorts of things – logo animations, shampoo bottles, car commercials, the logo animation for a game called Spellforce 3 in 2015.’

But he also needed, very strongly, to make work he personally connected to. ‘The idea to do art for myself grew.’ He began to shape his freelance life to allow space for his own work.

‘I’d do a job that would pay 8-10k, for a few months, then chill with a personal piece when I’d been paid well enough. I built up enough to do 1 or 2 of my own pieces a year.’

One piece of freelance work he’s proud of was something he did for NASA. ‘Dr Masahiro Ono, a researcher at the jet propulsion laboratory, wrote a paper on deep space travel, getting from Earth to the Kuiper Belt. He had an idea we could put a harpoon into one of the asteroids and then get pulled along. He asked me to ‘build’ the spacecraft. He said do whatever you want, we can’t actually build it, at least not in the next hundred years, so do what you want.’

But generally, he says, he’s a bad freelancer. He gets fixed in the detail, he wants to make the full potential he sees in his mind’s eye. ‘If a client is saying ‘can we do that’ I say ‘yes! ‘ and I want to spend four weeks on it but only have three days. I get burned out quickly.’

Eventually he decided to take a break from freelancing. ‘I got an anxiety disorder and couldn’t freelance any more. I needed to do something where I sat at a desk and did work, and left at 6pm. I got a job with Elastique, a tech company in Cologne and worked for them three years. They were really cool. I liked the people and the boss. and then…’

And then, just last year, he made a couple of big sales in the crypto market. 6088AD, the piece he made the tutorial of, which has been circulating around 3D artists since 2017, suddenly caught the attention of the NFT community. ‘Somebody asked to buy it. Then somebody bought the piece that’s on the Octane site too. So now I’m in the crypto-art market.’

These sales have bought him the creative freedom he’s sought so eagerly, but he’s aware that crypto-art is a thorny topic for some. ‘Everyone talks about crypto-art and NFTs and they hate it all… but it’s either that or working on commercials I don’t connect with. I don’t want to jinx it. For me it was always a dream to do what I want and make a living from it.’

The success was sudden, but it didn’t happen overnight. Cornelius has been nudging his work into visibility, slowly, over many years.

‘I was always in communities,’ he says. ‘Right from the beginning, when I started in digital art alone in my room, I was a member of an online forum. We were only a few teenage boys from Germany, but I showed them my stuff, they showed me theirs. I put my work on a website called Deviant Art, and MySpace, then grew to Instagram, then Twitter. In the beginning I didn’t have many followers but I’ve been on Twitter for over 10 years. Now I have 15k followers, though most of them came recently (tweet him at @planetzomax). On Behance, the portfolio platform, I didn’t have any followers at first but over 10 years it grew, then I got featured, then Substance did an article. Everything grew constantly, and grows constantly. I never had a plan, I was just uploading stuff. So long as it was good enough.

‘Everything in digital art is long term,’ he says. ‘All the good artists I know have been in the game for over 10 years. The crypto artist Beeple puts an image up every day and he’s been doing that for 15 years. It’s a marathon, not a sprint. In the beginning you’re unknown, but put in the work and people will recognise you, they’ll see you’re good technically. Though you need luck, it’s also time and skill.’

The long game has certainly paid off for Cornelius now. The pieces he sold recently on the crypto market were made in 2016 and 2017.

But something that hampers him is his love of detail. And epic scale. ‘I’m really slow. There are artists who do something in a week or two. I’m what they call a pixel peeper… I want to control every detail. I carry around an idea for four years, thinking about it every day, making notes, sketches, before I even do anything.’

If you work like that, how do you keep up with the Beeples? How do you keep feeding the platforms?

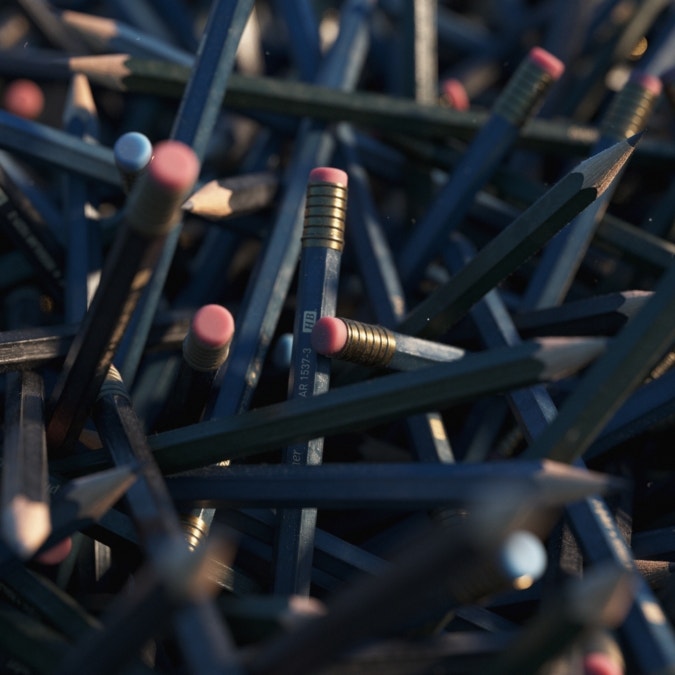

He found an answer – in smaller-scale projects. These are vignettes – a heap of syringes or graphite pencils, beautiful in their simplicity and love of shape, light and detail. He enjoys this new direction.

‘Sometimes the big pieces can be stressful and draining. Sometimes I just want to do a quick experiment to keep things fresh and have fun. It feels safer, more fluent because I only work on it for a week or two and it’s done. And if I focus on smaller things I can still keep up the quality. If I create one object in a black void it’s easier to focus all the details and craftsmanship. And the language the image speaks is different from the big images and I enjoy that. If I do a schoolroom with 50 computers it’s a lot of work and hard to focus on just one thing.’

What else feeds his imagination? Music is important. He’s close friends with electronic musician Lukas Guziel. Lukas has created soundtracks for his tutorial videos, and also for short, 1-minute videos Cornelius makes of the details in his still pictures. They riff off each other. ‘I create the video, show it to him, he creates music, I change the cuts in the video to work better with what he does in the track, he changes the music, cuts faster, or puts more space in the beginning. We influence each other. And Lukas makes music that pushes me to create.’

I ask him which artists or other creatives influence him. He cites the American electronic musician Lorn (‘he does really dark music’). Also Martin Stig Anderson who created the music for the games Limbo and Inside (‘these games also inspire me’). The illustrator and graphic designer Ash Thorp, a personal friend. The illustrator Piotr Jablonski (‘his technical abilities and the atmosphere of the images are perfect’). ‘I also like the old war photographers, and the street photography of Henri Cartier Bresson at Magnum. Because he can capture real moments.’

Photography

Recently he’s started taking photos himself, to widen his repertoire. ‘I bought a camera to expand my visual eye. At the moment, when I create something I play God. I can decide how tall a building should be or which direction the sun should go. A photographer, though, is in the scene, in real life. and has to decide the best shot. He can’t control anything. If I was coming into this room right now, what would be the right shot? I want to practise that. To see the right framing and the right moment so I can apply that to my work.’

He puts some of his pictures on Twitter. I see a familiar note in a pic of colourful block buildings at night.

Iceland

But another picture contains a new direction – a black beach with ice floes and eerie electricity pylons queuing into the distance.

‘I was in Iceland last December,’ he says, ‘and it’s beautiful. Landscapes without trees. A completely black beach with pieces of icebergs and electricity pylons in the fog – that alone could be an image. Super-moody and perfect.’

And since you’re wondering, the software he regularly uses is Adobe Photoshop and After Effects, Maxon’s Cinema 4D for 3D modelling, Otoy’s Octane for rendering, Marvelous Designer for cloth simulation. Other favourites are ZBrush, Substance 3D Painter, DaVinci Resolve and Fusion 360.

I ask what he’d say to working artists who want to start creating personal work. His answer: follow your interest. And experiment.

‘You start with art because you have drive. Something or someone inspired you and you thought, that’s cool. I want to do that too. So copy them. Get inspired and do whatever you want, it doesn’t matter what. Even if it’s too hard, try it out. Just do things.

He says it’s also important to think long term. ‘Remember the whole art thing is a marathon. So enjoy the moment. Also take breaks. It’s okay to. If you feel like taking two weeks off to play video games and that would be better for your mental health, do that. The judgement of whether your career was a success won’t be done by you, it will be done after you’re gone, and it will look at your whole body of work. It won’t matter if you had a break of three days because you wanted to play a new videogame.’

Also, don’t be fooled by the personas you see on social media. ‘There’s a work culture on social media that everyone has to work all the time. You see someone working 24/7 and you think if you don’t do that you’ll fail. Actually, everyone will fail all the time. Always. I would never trust someone who didn’t fail. I don’t think anyone’s perfect and we fail all the time and that’s how it should be. Especially in art. You try and try and try and sometimes you get it right and that’s the cool thing, then you’ll make progress. That’s okay, you fail your way up.

‘And also be humble. Don’t be a dick. There’s nothing worse than an arrogant artist. Know that you’re failing all the time and that you try and you don’t know the answer. It’s cool if you’re really good at what you do but still try to be humble about it because there’s always someone better than you.’

If you want to watch his mind in motion, look at his mood and concept boards on Pinterest. Many of the images there, he says, are cornerstones for artworks he will eventually make.