Discover applications of 3d modeling.

Learn about how designers, studios, and companies use Substance 3D.

Substance 3D in games.

Discover how the Substance 3D apps and content are used to create beautiful stories, from indie mobile games to AAA productions.

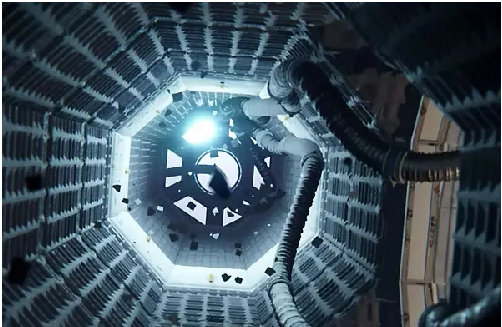

Substance 3D in film.

Explore the Substance 3D apps and content in the film industry, whether for animation or VFX in commercials and feature films.

Substance 3D in fashion.

Discover how fashion and apparel designers use the Substance 3D apps and content to create ultrarealistic clothing designs in a sustainable way.

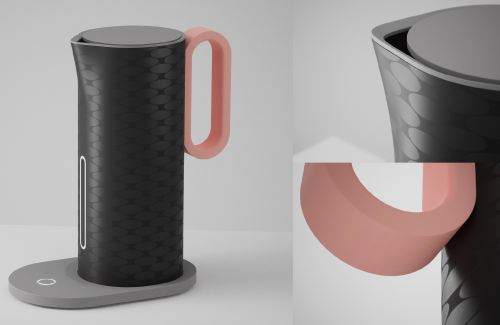

Substance 3D in product design.

Discover how Substance 3D can enhance the product design process and help designers create, from prototypes to high-end visualizations.

Substance 3D in architecture.

Create photorealistic architectural designs for real-time or AR projects, when you need to work fast without compromising on quality.

Substance 3D in automotive.

See how the Substance 3D apps and content can help car designers create exceptional, photorealistic visualizations.

Substance 3D in consumer packaged goods.

Learn how the Substance 3D apps and content help you visualize and manufacture your consumer packaged goods and support sustainable design.

3D rendering and Adobe Substance 3D.

Discover how the Substance 3D apps and content can improve your 3D rendering work.

3D texturing and Adobe Substance 3D.

Find out how the Substance 3D apps and content can help your 3D texturing work.

3D lighting: Types of lighting and 3D lighting techniques.

Learn about the basic techniques for 3D lighting as well as a different type of 3D lighting.

Virtual photography and Adobe Substance 3D.

Learn what virtual photography is and how the Substance 3D toolset can improve your content velocity with virtual photography.

What is AR? Augmented reality explained.

Learn what augmented reality (AR) is and how it is being used more widely in different industries.

What is VR? Virtual reality explained.

Learn what virtual reality is and how it is being used more widely in different industries.

What is mixed reality?

Learn what mixed reality is and how it differs from VR and AR.

Industrial design: What it is and what industrial designers do.

Find out what industrial designers do in their day-to-day jobs.

Everything you need to know about physically based rendering.

Want to learn about physically based rendering (PBR)? Read this article to learn about PBR and how it relates to photorealism.

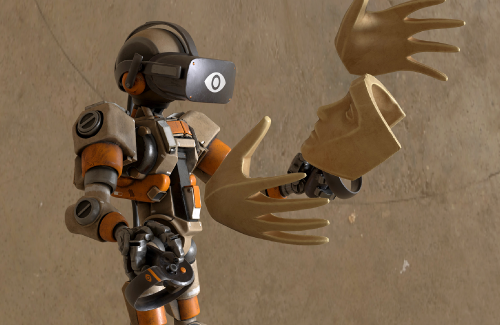

3D character creation & design software.

Whether 3D characters are made for games, movies, or art, artists need the right software to get the job done well.

A guide to 3D file types.

There’s no one size fits all solution to file formatting. Here’s everything you need to know about file types and how to use them.

Creating 3D models from videos: is it worth your time?

Videogrammetry is a measurement technology that gathers 3D information from video footage to create a 3D mesh.

Learn how to create 3D textures.

Working with textures is a crucial step in 3D modeling. Everything from color to physical appearance is controlled by texturing or applying materials.

What is 3D modeling?

3D modeling is the process of creating 3D objects using specialized software. These models can be staged with other visual effects to create entire scenes for still imagery or animation.

How to make 3D Furniture Models.

3D furniture design is used for more than populating video games with realistic props. Many design pros and e-commerce websites use 3D models to help showcase and sell their products.

How to make 3D architectural models.

If you’ve toured a digital home, you’ve experienced the power of 3D and AR. 3D technology is making waves in many industries—architecture is no exception.

How to create art using Adobe Substance 3D.

Give your art that extra dimension—namely, 3D. Create lifelike 3D images and renders of anything you can imagine with the power of the Adobe Substance 3D apps.

How to make a 3D model from a picture.

Anyone can create 3D models from photos with the help of Adobe Substance 3D Sampler in just a few steps.

What is a polygon in 3D modeling?

Polygons are 2D shapes that are used to create 3D meshes.

What is 3D visualization?

3D Visualization refers to the process of creating three-dimensional images of objects, environments, or data using computer-generated graphics.

What is normal mapping?

This technique is used to create illusory surface details to enhance the realism of digital objects without increasing geometric complexity.

Learn the foundations of 3D.

Jump-start your creativity with videos designed to teach key 3D concepts.

Discover the world of Substance 3D.

Get content, get inspired, get creative.

Asset library